Wiradjuri Culture

People of the 3 Rivers & carers of the land

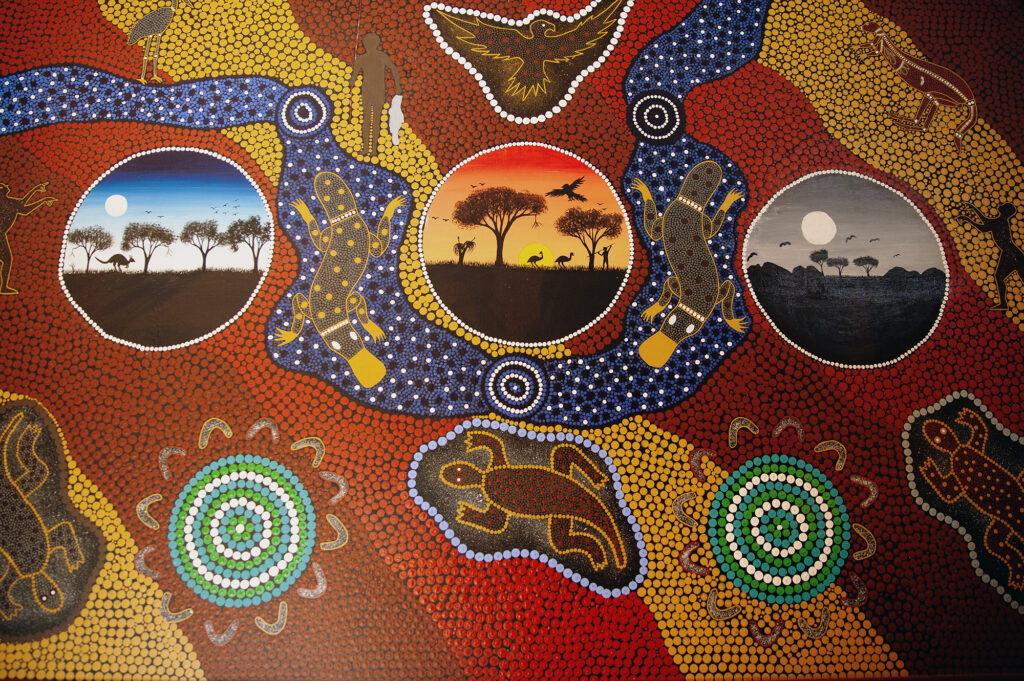

Geographically the largest indigenous nation within NSW, Wiradjuri have been custodians of the land for 40,000 years. They have lived in harmony with the environment taking only what was needed. They were caretakers, respecters and protectors of the environment they belonged to.

About the Wiradjuri Nation & Country

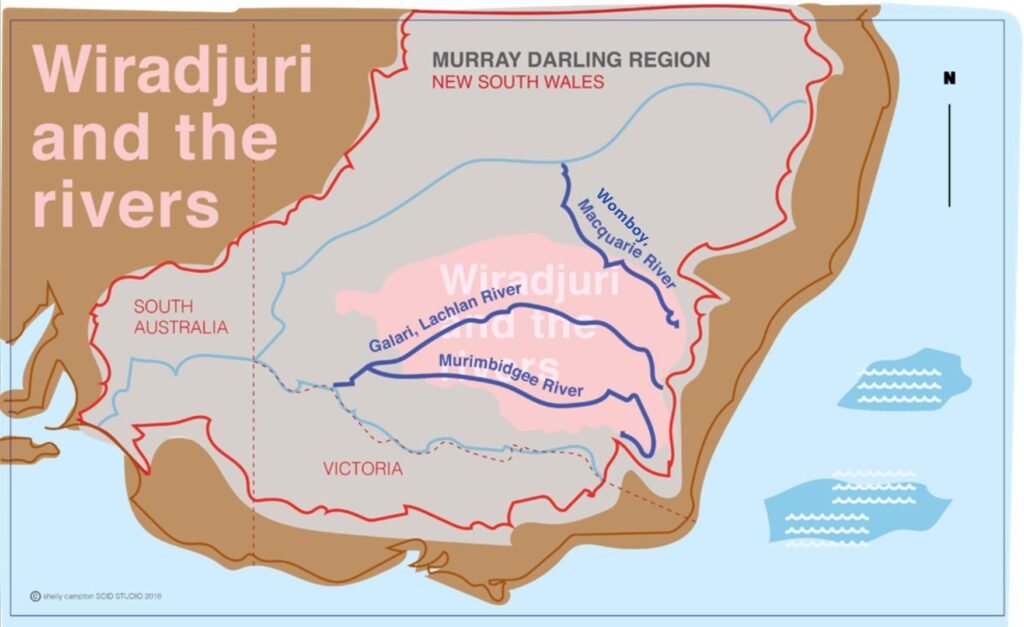

Land of Three Rivers

- Murrumbidgee (Known by its traditional Wiradjuri name)

- Gulari (Lachlan)

- Womboy (Macquarie)

The territory covers hills in the east, river floodplains, grasslands and mallee country in the west. These environments provided all the materials necessary for survival as hunters and gatherers. On the floodplains there were rivers, creeks, billabongs, swamps and lakes which contained many fish, yabbies, mussels, crayfish and tortoises. The waterways were home to many wetlands birds, such as teal, wood

duck, ibis and water fowl. Following the winter floods there was plenty of food for a long time.

Traditional Life

Wiradjuri have been custodians of the land for 40,000 years. They have lived in harmony with the environment taking only what was needed. Groups of men, women and children travelled in groups following the seasonal availability of food and resources. Men and women would hunt and gather what they needed using many tools, weapons and methods.

Dreaming was very important. It is through dreaming that traditional ways were followed. Dreaming explains how the land, animals and plants were created. It also describes how people should act and behave.

People did not own the land but were responsible for looking after it. Each group had their own area to hunt and gather food. The size of the area varied according to the amount of food in it. A group would consist of maybe 10 to 50 people depending on food supply and other things. Each group was based on family groups and relationships held to extended family groups.

The Wiradjuri nation was made up of hundreds of groups living throughout the territory. These groups had the same language and the same beliefs. That is what made them a nation.

Each of the people had a specific relationship with the others in the group and the nation. The relationship rules came from the Dreaming and told them who they could marry and how they should live. It is how they got their totem. The dreaming also told of the ceremonial places that were sacred. The kinship rules meant that no-one would ever be alone without someone to care for them.

Society was built around religion and spirituality. Baiame was the creator and gave the laws for behaviour and custodianship of the land.

Children learnt about life and ceremonies as they helped with the daily work. They would learn how to hunt and gather food by helping the women and men. As the children grew older they were taught more and more of the group’s secrets. Education was a life long process. It was the women of the group who were responsible for teaching the children.

Children learnt about life & ceremonies

Photo credit: Marion Wighton Packham

The group was semi nomadic and moved camp to follow the food supply of the seasons. During the cold time they wore a fur skin from a possum or kangaroo around their shoulders to keep warm. Summers were hot so they wore a woven skirt or went naked. The pattern of life was determined by the seasons.

For the boys an important time was their initiation. The initiation was carried out in a large ceremony called a Burbung. Invitations would be sent to neighbouring groups and even to other nations. Planning and preparation took many months. The burbung ground was prepared by clearing and marking trees. Guests arrived and camped facing their country. The ceremonies began when everyone arrived. The young boys were taken into the bush for training, testing and initiation into the next level of knowledge. Each boy would go through several initiations in their life before adulthood.

Corroborees were performed by each group. Bonds with each other and the spirits were strengthened. The Wiradjuri council would sit during this time to discuss important issues and set laws.

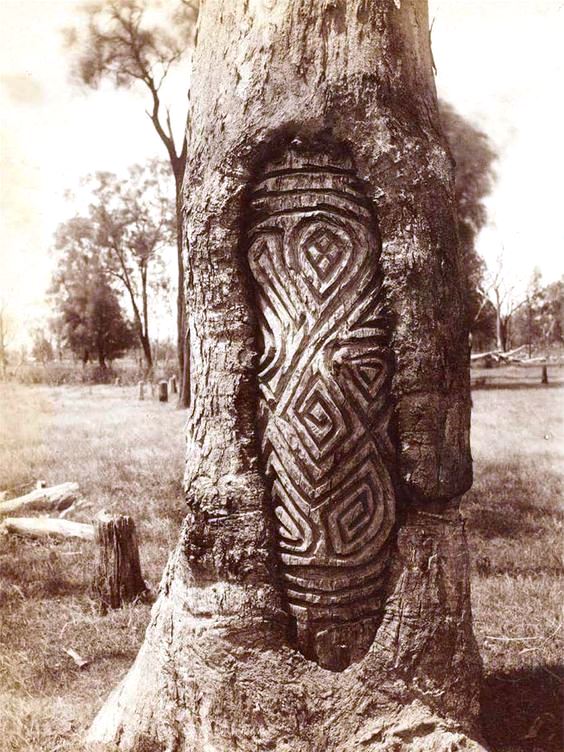

There are many sacred and important sites within the Wiradjuri area including ceremonial sites, carved trees, bora grounds, burial sites, dreaming sites and initiation areas. These sites were special areas where they could connect with the spirit of the lands.

Two important sites for the Wiradjuri people within the Lachlan Shire are Mana Mountain & Goobothery Hill, The King’s Grave.

Traditional Cultural Aspects

Some totems are listed below:

Windbreak

Used in summer or while travelling. It could be set up quickly and left when the group continued on the next day.

Lean-to

The most common shelter.

Each family would have their own gunya in the camp. It is waterproof. A fire could be lit outside for warmth

Mia-Mia

Weatherproof shelter used in cold seasons. A family of 4 or 5 would

sleep inside with a small fire at the front

To keep warm they would light a few small fires, not big ones, around the group and sit between them. This was better than having one big fire because all the body was warm not just one side.

Quandongs

Quandongs were eaten along with fruits of the “bush tomatoes”

Emus

Although hard to kill, emus & kangaroos provided plenty of meat

Witchetty Grubs

Women & children hunted small lizards & witchetty grubs

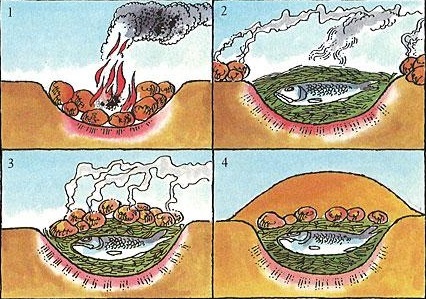

The main meal of the day was in the evening when the while group was in camp. A fire was lit to heat up clay balls that were made from the river clay. These balls were about as big as a cricket ball. If there wasn’t any clay near the camp small rocks would be used.

Campsite pit with clay balls

Cooking process

Clay balls

Wiradjuri grooves

Wiradjuri grinding grooves & sharpening grooves can be seen at Manna Mountain located in the Lachlan Shire

Woomera

A tool used to throw a spear very accurately over a long distance. Made from a piece of wood cut from a tree.

Boondi

Used for hunting and fishing and one of the most deadly tools. Made from Mulga, Gidgee, Yarran or Ironbark wood

Shield

Very important and used in ceremonies and fighting. Made of hard wood with a strong handle

Digging Stick

Used by women to dig up roots, burrowing animals and grubs. Made from very hard wood

Boomerang

The Wiradjuri mae for boomerang is “Baddawal”. Boomerangs were used to hunt, to dig, used as clapsticks to make music, used in fights and even used to ligh fires by some of the old men.

Coolamon

A dish like a bowl or pot. Used by women to carry water or food. Some woman would balance them on their heads. Made from the elbow of a root or branch of a tree.

Bullroarer

A flat piece of wood shaped and decorated by the owner. It was attached to a piece of string and swung around to make a unique sound. Used to warn people to stay away when men’s business was taking place & used by children to let their parents know where they were.

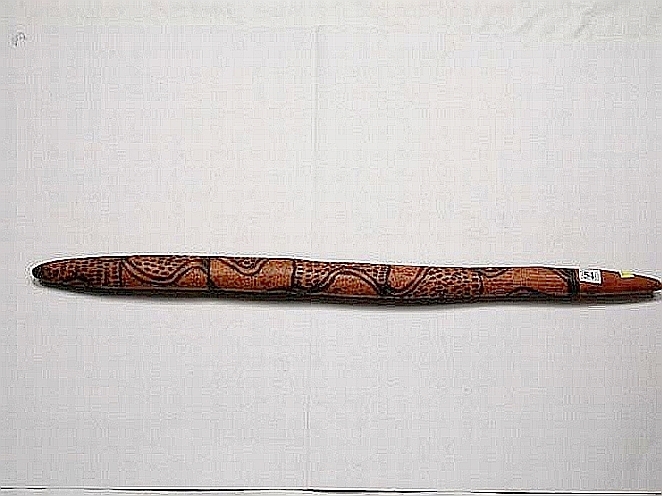

Message Stick

When travelling through another groups area people carried a message stick. The message stick explained who the person was and why they were travelling. It

ensured safe passage, ifcaught in another groups area without permission there would be trouble.

Canoe & the Canoe tree

- Trees which have some bark removed for use;

- Trees which have some wood removed for use;

- Trees which were cut in some way to make climbing them easier; and

- Trees which have a design carved on them.

the base of the tree to flush out the possum.

Carved Tree

Ring Tree

The photos are of weaving work by Bev Coe and the ladies of Sista Shed in Condobolin

Photo Credit: Marion Wighton Packham

Acknowledgement

Much of the information on this topic above has been sourced from Paul Greenwood’s book “Land of the Wiradjuri” which was developed as a resource to assist in understanding the Wiradjuri traditional culture. Although the book is intended to provide information on Wiradjuri culture, some information is generic to the Aboriginal culture.

The Murie in Condobolin

Acknowledgement:

The following information was posted by the “Wiradjuri Mob” 2nd January 2015.

The Murie Elders Group are passionate believers in the preservation of local history and culture. The group has been working for a number of years to protect and preserve the cultural knowledge of The Murie. It is regarded as a very special place and The Murie ‘will always be home’ for many people.