Wiradjuri Arts

Promoting cultural understanding & awareness

The Wiradjuri Study Centre offers a local hub for training, development and employment, cultural appreciation, cultural awareness and heritage issues. It offers a keeping place and a space to yarn up.

About the Wiradjuri Study Centre

The Wiradjuri Study Centre was constructed with the express purpose of promoting the study and understanding of Wiradjuri culture and provide training opportunities for people within the Wiradjuri Nation and surrounds.

The centre offers a local hub for training, development and employment, cultural appreciation, cultural awareness and heritage issues, a keeping place and a space to yarn up. It is also the headquarters of the Wiradjuri Condobolin Corporation. The corporation itself was established in 2003 to implement the provisions of the Ancillary Deed on behalf of Native Title Party, and to create a better quality of life for the people of the Wiradjuri Condobolin community. This is being achieved by self determination and empowerment of their community; through economic, social and cultural development; education, employment, sporting, vocational and skills development.

The Centre is a circular complex of buildings made from compressed earth bricks surrounding a central courtyard. Statues adorn the beautiful gardens and a dance circle also highlights the importance of this centre.

WSC state: “The building is an iconic centre for Aboriginal cultural understanding, learning, research, training and wellbeing. The process begins by the fact that the building has been constructed by teams of local Aboriginal people using materials they either have made (eg compressed earth blocks), or are local to the region (eg cypress timber), and all is consistent with sustainability and caring for country principles.

It is accessible to interested non-Aboriginal students and visitors. With that end the WSC has the following components; Cultural Centre, Conservation and Environment Centre, Skills Development Centre, Indigenous Training, Wellness Centre, surrounding landscape and sporting facilities and a Yarn Up Space.”

Wiradjuri Study Centre

- Crn McDonnell & Cunningham Street, Condobolin

- 02 6895 4664

History & cultural aspects of the Aboriginal people in the area

The Aboriginal history of the area

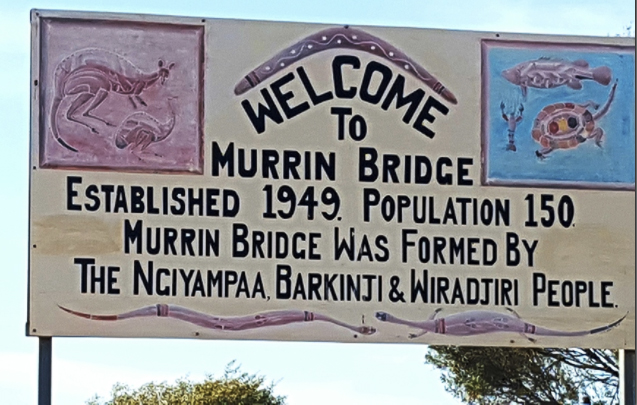

Murrin Bridge Aboriginal Station

From here they were moved to Menindee after the water supply at Carowra Tank failed.

Photo is courtesy of the State Library of NSW

Carowra Tank, 1924 – 1933

Carowra Tank became a central depositing Station for the remnants of central and western New South Wales traditional societies, as the Ngiyampaa speakers were joined by people with other languages, including Wiradjuri from the south as far afield as Victoria, and their fellow Ngiyampaa speakers from around Marfield Station.

The Marfield mob, or Geordie Murray’s mob as they were also known, were a “mob like a little wild family”, who built miamias outside the tin-roofed huts supplied by the government, in preference to living in them (Donaldson, 1977:16)

Corrugated iron for these buildings came in 1924, provided by the Aborigines Protection Board. In November 1925, the Board appointed a teacher-manager to control the settlement (Horner, 1974:20).

In 1926 Carowra Tank was established as a white-run Aboriginal Station (See Map 6). Here a new type of relationship with Europeans began. There were two female missionaries, described by those who remember them as “kill-joy people” who stopped them dancing, and the station manager, who removed the “lighter caste” children for education at “specially created institutions” (Donaldson, 1977:16).

The Aborigines Protection Board reported that the establishment of this Station was necessary because of the influx of a number of new settlers which deprived the aborigines of a great deal of their former freedom to roam and hunt over the big holdings and brought them in such closer contact with the white population that it seemed advisable to form a settlement where they could be concentrated and cared for (A.P.B.Report, 1926).

In that year the wool price dropped substantially and money was tighter in the sheep stations; unemployment as well as the drought forced more and more families to the Tank. The language, Ngiyampaa, was used by the large community at Carowra Tank as a lingua franca and this explains its survival.

The depression changed the living standards of almost everyone in New South Wales, but Indigenous people were particularly affected. Not only were they ineligible for unemployment benefits, but they also were discriminated against in sustenance allowances (Bell, 1959:350).

The government benefits for unemployed workers in 1930 was 5s. 9d a week for a single man, and rose to 7s a week in 1936. The food ration for Indigenous people cost 3s. 5d. a week and did not rise. The 1930 rate for the ordinary man, wife and child was 14s. 4d. a week, but for the Aboriginal husband, wife and child it was still 8s. 9d. in 1936. People who lived on Stations did not receive old age or invalid pensions (Horner, 1974:29-30).

The high unemployment reduced a number of families who had previously lived independently to seek these government rations at the Carowra Tank settlement – among them a number from Hillston and the Darling River (Beckett, 1966:13). This class of Aboriginal pastoral workers and casual labourers was most vulnerable to the vicissitudes created by the working of the wider economy. They were a people who paid a heavy price for their political and military defeat. They were stigmatised and disinherited. Australia is the only one of the England’s ex-colonial countries to have not legally “. . . upheld the basic principle of recognition of the title of their indigenous people” (Hocking in Olbrei, 1982:207-220).

Menindee Mission in its very early days, January 1934.

The large population afterwards suffered a serious decline as disease ran through the community.

Photo is courtesy of the Paakantji Menindee Community website

Menindee, 1934 – 1948

By 1934 the water supply at the Tank was becoming inadequate to support the community and the Aboriginies Protection Board removed the entire community to Menindee. This was a devastating experience for the people: many of their relatives could not be notified, possessions were left behind in the hurried exit, and they were forced to share squalid conditions with their traditional enemies, the Darling River people (the Paakantji).

They were also forced to camp at an old burial site; and the bone-dust was feared as a source of traditional poison and sorcery. Many people died at Menindee, some moved on to adhere to stations or towns in the west. The deplorable conditions at Menindee were revealed to the press by the Rev. T.E. Jones of the Bush Church Aid Society. He wrote of 250 people in the forty iron huts, twelve by twenty feet, with neither furniture nor facilities, most with earthen floors. A third of the reserve land was a long sand ridge, quite useless for anything. After the long colonial process they were totally in the control of the dominant white administration. As a crowning stupidity, two tribes which detest each other are together. As a result, many natives believe, rightly or wrongly, that some of the thirty-six deaths have been due to poisoning Jones, in Horner, 1974:74)

Questions were asked in the House about the frequent deaths, which were attributed to either tuberculosis, or the peoples’ fear of the lethal qualities of ‘bone-dust’ (Horner, 1974:74). The government reported in September, 1938, that: “The 180 Aborigines of the Menindee station and the buildings, etc. cost £60,000 including a picture theatre” (Barrier Daily Truth, 27-8-1938; in Horner, 1974).

In June 1974, work finally began on the new Murrin Bridge Station near Lake Cargelligo. William Ferguson, the Aboriginal activist, expressed his disgust at the lack of any bathrooms in the cottages, for the project was expected to be a model village (Horner, 1974:141). There were to be thirty-eight houses, two staff residences, a medical block, a recreation hall, a church and an administrative hut.

Murrin Bridge, 1949

The Move to Murrin Bridge, 1949

When the village was finished in early 1949, the people at Menindee were sent by train 240 miles east to Euabalong and then by truck to Murrin Bridge, sixteen years after the first panic-stricken journey west from Carowra Tank. This second journey, while being less traumatic than the first, was related to me with great feeling and some amusement, for they were in charge of a young inexperienced cadet welfare officer, and dogs fought and barked, people argued, and confusion reigned in regard to the organisation of the journey, carriage of possessions, and the nature of the new settlement.

Most of the Carowra Tank people were content to go to Murrin Bridge while the majority of the Paakantji preferred to live independently at Menindee or Wilcannia. At least ten marriages had taken place between the two groups and when the Menindee Community split most of the husbands followed their wives’ people (Beckett, 1964:13)

The Aboriginal Mural on "Fisho's" Wall

Aboriginal Mural - A symbol of Reconciliation

Fr Emil Milat blessing the Aboriginal mural

One of the students palm painting as part of the mural artwork

During painting of the mural

Artists

The following is an extract from a story submitted by St Francis Xavier Primary School Lake Cargelligo for the "Catholic Voice" - 11th February 2019

“Year 5 / 6 students from St Francis Xavier School were lucky enough to participate recently in designing and painting an Aboriginal mural.

This project is a result of an Arts Out West grant which supported local artists Lindsay Kirby, Tanya Harris and Georgina Kelly under the coordination of Sandon Gibbs-O’Neill, an Aboriginal artist and Community Engagement worker at Lake Cargelligo TAFE.

The students attended a Mural skills workshop at TAFE where, along with secondary students (from Lake Cargelligo Central School), they learned painting techniques and contributed their design elements and ideas for the mural. The adult artists then combined all the students’ ideas and came up with the design.

The Aboriginal mural was blessed by Fr Paul (Anglican priest) and Fr Emil. The blessing ceremony commenced with Josie Thorpe sharing a welcome to country with all present, then Fr Paul and Fr Emil shared some special prayers, asking that the mural be a symbol of Reconciliation and a continued way forward for our community working together.

All that were involved and the mural were then blessed, before Sandon Gibbs-O’Neill, the project coordinator concluded the ceremony by thanking all that were involved and congratulated them on their work, the extra efforts put into completing the mural and the co-operative nature of the work with elders and the students from Lake Central School and St Francis Xavier School.

This project was a result of a successful grant organised by LLCS through the funding body- Arts Out West (CASP- Country Arts Support program) grant. “We would like to thank all those involved in the project that enabled our students to work with so many talented artists to create a mural that will be a focal point in our community forever,” stated Mrs Jacinta Elwin. “Our students learnt so much about the process of design, painting techniques and working together as a community.””

The following is an extract from the Lake Cargelligo Central School News - 2nd November 2018

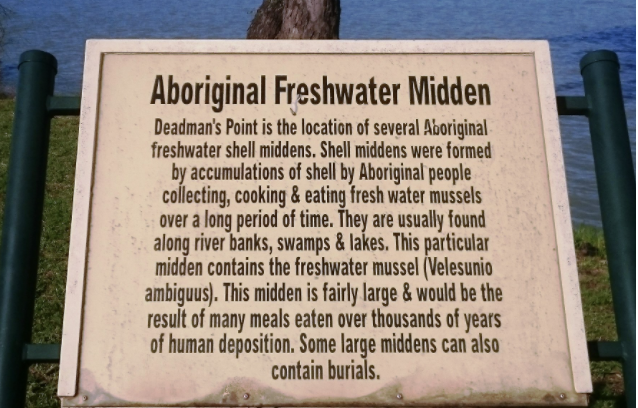

Aboriginal Freshwater Midden

Deadmans Point

Ochre pits can still be found on the Lake's edge at Frog's Hollow

Frog's Hollow freedom camping site

Aboriginal Freshwater Middens at Deadman's Point

Ochre Pits at Frogs Hollow

The name Lake Cargelligo is a variation of “Cudjallagong” which in the Wiradjuri language means ‘Lake’. The area is rich in aboriginal history as the Wiradjuri tribe gathered on the banks of the lake for generations prior to it being discovered by Oxley in 1817. Many years ago, the Lake Cargelligo area was a meeting place for Aboriginal people. An aboriginal quarry containing rich yellow and red ochres which was used for ceremonial markings can still be visible at an area on the lake’s edge at Frog’s Hollow. Due to the presence of relatively permanent water, the lake and some parts of the Lachlan River were used by the aboriginal people for centuries as meeting places and sources of food and water. Many Aboriginal artefacts have been found on the lake foreshores. The ochre from the pit was used by the local indigenous population to decorate themselves during corroborees, for Aboriginal painting, and for decorating didgeridoos which were a valuable trading commodity.